Broadband, Digital Equity and Local News

In a proposal to the U.S. Department of Commerce, Rebuild Local News and Prof. Christopher Ali suggest why “digital equity” programs should strengthen local news — especially in the “double deserts” that lack both broadband and strong community information

The U.S. Department of Commerce asked for comments about how to implement the Digital Equity Act, approved as part of the 2022 infrastructure legislation. Working with Professor Christopher Ali, an expert on the topic, Rebuild Local News recommended that since digital equity involves ensuring that residents can participate in civic life, it’s crucial to also strengthen local news. Decades of research on the decline of local news shows the relationship between local journalism and civic participation, ranging from volunteerism to voting habits. In addition to their civic function, some local newsrooms provide digital and media literacy training or participatory journalism opportunities that support digital equity objectives.

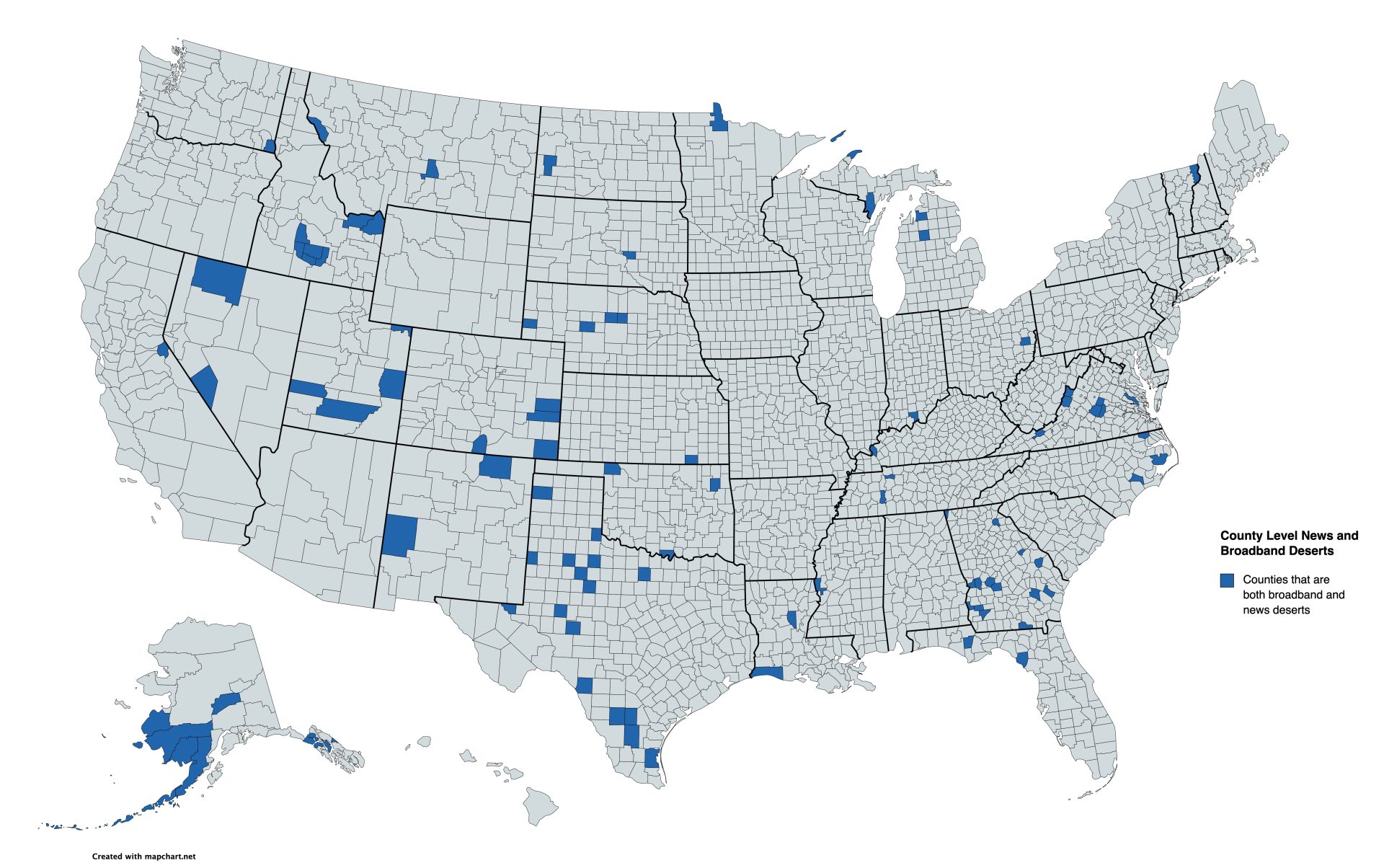

In preparing this proposal, Ali and Pennsylvania State University doctoral candidate Ryan Want discovered a disturbing phenomenon — the persistence of “double deserts,” counties lacking both adequate internet service and local news sources. Between 43% and 45% of news deserts did not reach the minimum speed threshold and all of them were considered underserved by broadband resources. The communities that are least likely to have local news are the same communities that are most likely to lack access to affordable, quality broadband. Our proposal argues that improving broadband without also strengthening local news may make matters worse, providing high-speed access to low quality information. The Digital Equity Act is currently being implemented in partnership with states.

Submitted to: U.S. Department of Commerce (USDOC) National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA)

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) Digital Equity Act of 2021

NTIA 2023-0002 Docket No.: 230224-0051 RIN 0660-XC055

Introduction

The NTIA asks for comments regarding what entities and projects the Assistant Secretary should consider as eligible and ideal for digital equity program funding. We argue that local news organizations and projects can be a significant partner in digital equity strategies.

We see two realities that should shape policy making around digital equity and local news.

First, many areas lack both adequate broadband and adequate local news. They are both broadband deserts and news deserts. Indeed, our research finds that of the 196 counties identified as “news deserts” by noted journalism professor, Penny Abernathy, between 86 and 90 – between 43% and 46% – are also “broadband deserts,” meaning that residents lack connectivity at FCC-defined speeds of 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload. Moreover, not one of these news deserts (where speed test data were also available) gets even close to the 100 Mbps download/ 20 Mbps upload underserved standards set by the Infrastructure Act.

If we only solve one part of this problem by providing affordable high speed internet access, but fail to provide trustworthy local information we will not be enabling residents to be full participants in civic society. Achieving “digital equity” means, in part, all residents have high-speed, affordable access to reliable information about their communities, not just entertainment, social media and government websites.

Even worse, in information vacuums, residents may turn to social media or partisan news, increasing the likelihood that misinformation and polarization will spread. Without also addressing the collapse of trustworthy local news, more broadband access may lead to what one expert called, “high speed access to Internet garbage.” What’s more, the arrival of broadband is a mixed blessing for many local news outlets. While it offers residents greater access to information and news outlets greater tools to reach their audience, it also offers local businesses a free — or at least cheaper — alternative to advertising in local news outlets, meaning small but enterprising news outlets must compete with platform resources. Of the 26 news outlets we surveyed, 59% said that when broadband comes to their communities, local businesses are less likely to advertise in their news outlets and more likely to use social media to reach their customers.

That’s why these news and broadband deserts, or what we call “double deserts,” need to be confronted together. Both local news and accessible, affordable broadband are important pieces to ensure citizens can participate fully in their cultural and civic institutions, but the arrival of one, broadband, can complicate the health of another, credible local news.

Second, in the communities that do have local news organizations, they often are trusted community institutions well suited to advance efforts around digital literacy. Indeed, in many areas, local news organizations are already helping residents learn how to use technology and the internet.

Consequently, we make these recommendations responding to the NTIA’s questions regarding State Digital Equity Plans, Digital Equity Capacity Grant Program; and the Digital Equity Competitive Grant Program:

Regarding the Competitive Grant Program, the Assistant Secretary should include local news organizations as an entity that is “in the public interest and is not a school” (Section 60305(b) of the IIJA, page 13104 of the Notice). Doing so would both recognize the vital connection between local news and digital equity, and the role that local news organizations can play in fostering digital inclusion initiatives.

Second, also regarding the Competitive Grant Program, initiatives to strengthen local news should be included as eligible organizations to advance digital equity.

Third, related to State Digital Equity Plans, the Capacity Grant Program, and the Competitive Grant Program, increased civic engagement should be included as a metric of impact and success of certain digital equity programs.

And finally with regards to State Digital Equity Plans, the Capacity Grant Program, and the Competitive Grant Program in “double deserts,” local news organizations should be strengthened in order to help achieve those civic engagement goals.

Digital equity requires reliable local news and information

Section 60302(10) of the IIJA defines “digital equity” as “the condition in which individuals and communities have the information technology capacity that is needed for full participation in the society and economy of the United States.” To achieve digital equity, communities must engage in digital inclusion efforts. Section 60302(11) defines a crucial component of digital inclusion as having access to, and the use of… (iii) applications and online content designed to enable and encourage self-sufficiency, participation, and collaboration.”

Access to local news and information through trusted news organizations fulfills this third criteria of digital inclusion. Local news organizations provide what many have called “the critical information needs of communities.” According to Lewis A. Friedland, in a literature review submitted to the Federal Communications Commission critical information needs are: “Those forms of information that are necessary for citizens and community members to live safe and healthy lives; have full access to educational, employment, and business opportunities, and to fully participate in the civic and democratic lives of their communities should they choose.” There are eight categories of critical information needs:

- Emergency and Public Safety

- Health

- Education

- Transportation systems

- Environment and Planning

- Economic Development

- Civic information

- Political life

Local news outlets help meet these information needs. They provide information about elections, extreme weather, disease information, new local businesses, school board meetings and so much more. Tragically, in the last two decades the value and contributions of local news has been best captured by what happens in communities when local news either recedes or disappears entirely. As Rebuild Local News wrote in a submission to banking regulators:

Communities with less local news end up with a more dysfunctional political system, which makes it harder to solve local problems. Communities with less local news have lower voting rates, fewer contested races. In Cincinnati, after the closure of a city’s second newspaper, the Cincinnati Post, fewer candidates ran for office, “incumbents became more likely to win reelection, and voter turnout and campaign spending fell.” Residents in areas with less local news are less informed about elections. A decline in local coverage (based on a study of 10,000 articles from 2010 to 2014), led to voters being less likely to have an opinion about their member of Congress. They are less likely to be able to name things they like or dislike about their representative, less likely to be able to place their representative on an ideological spectrum, have less knowledge about public officials, and were less likely to Google the mayor, (according to News Hole by Danny Hayes and Jennifer Lawless). Conversely, those who regularly vote are more likely to follow local news (52% of regular local voters, compared to 31% of those who do not always vote).

Less civic engagement: In such communities, residents are less engaged in civic life, which means it’s harder to solve problems, and people feel more alienated.

Conversely, in communities with healthier and more inclusive local news systems, people feel better about their neighborhood and neighbors. For instance, after the closure of newspapers in Seattle and Denver, there was a significant drop in the likelihood that people would volunteer in civic organizations such as the PTA, the American Legion or a neighborhood watch. Conversely, those who follow local news closely are more likely to engage in activities with civic organizations such as sports leagues, church groups or charity organizations’ civic activities. In addition, Americans who have a close attachment to their community are twice as likely to be regular local news consumers as those with minimal attachment.

Less well-functioning local government: There is even academic evidence that proves what one would intuitively think: Less local news leads to less effective government and worse municipal services. Communities with less local news had lower bond ratings, higher financing costs, and higher taxes. They have more government corruption, and more government waste. Those districts get less government spending on public benefits.

Impaired public health and more corporate crime: These information gaps literally lead to challenges with the physical health of residents. For instance, communities with less local news are more likely to have more toxic emissions. Public health officials say the decline of local news has made it more difficult to track disease outbreaks. Companies are more likely to have serious regulatory violations — including environmental and workplace infractions — in communities that have lost local news coverage.

In sum, after reviewing the academic literature on the decline of civic participation, Professors Jennifer Lawless, John Harris and Danny Davis in News Hole: The Demise of Local Journalism and Political Engagement, conclude that most analyses of the decline in civic participation “don’t account for the most dramatic change in the civic life us communities have experienced in the last 20 years: the decimation of the local news media.”

Professor Abernathy concludes: “Strong local news organizations nurture both grassroots democracy and societal cohesion by providing critical information that helps residents in communities—large and small, urban and rural—craft solutions to their most pressing issues and make wise decisions that will affect the quality of their lives and that of future generations. Local journalists cover the mundane, but often consequential, school board and county commissioner meetings, as well as celebratory community events that nurture a sense of belonging.”

Local news organizations contribute not only to knowledge about a community, but also help to foster and “maintain a sense of community.” Their role in fostering civic engagement and voting has also been well documented. A 2016 Pew Research Center study, for instance, found that those who regularly follow local news are more likely than those who do note to be highly attached to their community, regularly vote, and actively participate in local groups and political activity. Conversely, the removal of a news organization from a locality diminishes civic engagement. Many experts on broadband access have noted similar benefits to broadband access. Christopher Ali, for instance, argues that broadband access in rural areas helps advance: economic development, health, education, civic engagement and quality of life. Echoing the contributions of local journalism to civic engagement, numerous studies have demonstrated how the adoption of broadband in local communities can lead to greater local civic engagement.

Trustworthy information and news about civic matters is become harder to find

In the past two decades we have seen a collapse in local news. Some 2,500 newspapers have closed since 2005, roughly a fourth of the newspapers in the United States. If the rate of closures continues, the U.S. is on track to lose a third of its newspapers by 2025. Roughly 1,800 communities that used to have a local news source now have none. The number of newspaper newsroom employees has plummeted by 57% since 2004. This has created thousands of “ghost newspapers” that barely cover the community. One study showed that only 17% of the articles in local newspapers were about local civic affairs. Some local newspapers have literally no local reporters at all. Gannett, the largest chain of local newspapers in the United States, has left papers from Salinas, California to St. Cloud, Minnesota, without local staff, instead relying on content from other Gannett-owned papers or wire services to fill their pages.

A lack of broadband infrastructure in these areas means an inability to access online news. As a result, the print edition becomes even more vital. The closure of these outlets means that the community becomes a news desert. As the Carolina Public Press recently concluded:

The ability of digital news to fill gaps in declining print-based media is hampered by this increasing digital divide. This disproportionately impacts rural communities where broadband access simply does not exist, leaving residents without essential news and information.

This problem is not limited to rural areas. Madeleine Bair, founder of the nonprofit newsroom El Tímpano, which services Latino and Mayan community members in the Bay Area of California, wrote to Rebuild Local News that “the digital divide and broadband access is not just an issue facing rural communities, but significantly impacts low-income communities of color, especially immigrants, in urban areas where affordability rather than broadband access is the greatest barrier to get online.” These barriers often mirror historic inequities related to access to resources, not just broadband resources.

The internet’s arrival has been a mixed bag for news consumers. It has provided residents with unprecedented access to news from around the country and world. It has enabled a much wider variety of voices to publish and be heard. Yet, it has also undermined the business models of local news organizations. Classified advertising dramatically declined, as residents could advertise cars, couches, jobs and houses more effectively and less expensively online. Then small and regional businesses concluded that they could better target their advertising using Google, Facebook or programmatic advertising. This shift has caused an economic crisis in journalism, notably for local newspapers, where so-called “analog dollars” are replaced by “digital dimes.” It’s not impossible that in some cases, therefore, the arrival of broadband in new communities could actually worsen the local news system by undercutting the advertising models of local newspapers, making it all the more important to include local news outlets – both print and digital – within the scope of digital equity to ensure access to local information along with broadband expansion.

Indeed, in our survey of just over two dozen news outlets, publishers reported that for all the benefits of broadband, when communities in their area have gotten high speed connectivity, more than half said they noticed more misinformation. By engaging in digital inclusion programs, local newspapers are well positioned to work with community members to combat mis- and disinformation.

News deserts are also broadband deserts

In 2018, journalism scholar and professor Penelope Abernathy, then the Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics at the University of North Carolina and now visiting professor at Northwestern University Medill School of Journalism, Media, and integrated Marketing Communications released data on what she termed “news deserts.” According to a 2018 report, The Expanding News Desert, Abernathy and her team defined a news desert as “a community without a local newspaper” and as “communities where residents are also facing significantly diminished access to the sort of news and information that feeds grassroots democracy.”

Thanks to the generosity of researchers at UNC’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media, we analyzed a dataset from 2020 of 196 counties they consider to be “news deserts”, those lacking a newspaper. We then compared these counties against speed data reported by both Ookla and M-Lab (data sets are from 2020 and taken from the NTIA’s Indicators of Broadband Need map).

We found that of the 196 counties that in 2020 were considered news deserts (the number has since grown to 211), between 86 (Ookla) and 90 (M-Lab) counties are also broadband deserts, which we define as lacking access to the internet at broadband defined speeds of 25Mbps download/ 3Mbps upload (of the 196 counties in our news desert dataset we lacked broadband data for approximately 79) . We estimate that between 43.8% and 45.9% of counties where data is available are “double deserts”, meaning that they lack both broadband access and local news (see Image 1). What is worse, none of the counties for which we had broadband data reported speeds anywhere close to the 100Mbps download/ 20Mbps upload standard set for “underserved” communities by the IIJA.

Image 1: County Level News and Broadband Deserts

The market conditions of local journalism and broadband access are quite similar, in that rurality and income are key predictors of both. Rural, Tribal, low income, and ethnic minority communities are least likely to have access to affordable broadband and many of these communities may also lack access to fresh local news and information. As Abernathy writes, “More than 500 newspapers have been closed or merged in rural communities since 2004. Most of the counties where newspapers closed have poverty rates significantly above the national average. Because of the isolated nature of these communities, there is little to fill the void when the paper closes.”

In a published academic study of Surry County, Virginia by Ali and Prof. Nick Matthews, one such “double desert”, the authors found that residents must perform a significant amount of extra work compared to their well-connected and locally informed neighbors. For instance, residents often rely on neighbors that are connected. Many residents cited the Dollar General or auto part store as their central “information hub” because that’s where they were most likely to bump into neighbors or friends who might have local goings-on worth sharing. This practice was made difficult by the Covid-19 pandemic – at a time when local information was arguably never more important. And even when locals were able to exchange local information in informal, community settings, they conceded there were likely significant gaps or biases in their awareness. One interviewee told researchers:

“Depending on who I talk to, I’m probably missing out on a bunch of information. I’m going to get the biases of the people that are providing that information. If a person that I talked to in reference to the bike path hated the bike path, then I’m sure they only told me about all the negative aspects that I had with it.”

The pandemic also showed the limits of strengthening broadband deployment without strengthening local news offerings. Some residents of Surry County were able to access Covid-19 case rates via government websites, which did break out data for Surry County. But no news outlets broke out or analyzed data on Surry County specifically, meaning Surry County residents were entirely dependent on government accounts, lacking the accountability local news outlets can offer.. Residents noticed the lack of accountability applied to official government reports. “People just get on (Facebook), and put what’s going on, but you never know what you’re missing,” an interview subject told researchers.

What would happen if we were to address a broadband desert but not the shortage of local reporting? At a minimum, we will not meet the full promise of universal broadband. Residents, like those in Surry County, will certainly have better access to the websites of government agencies, businesses, schools, health care providers and regional or national news (not to mention entertainment and national sports). They will also have better access to community social media platforms like Nextdoor or Facebook Local groups, which do provide an opportunity for neighbors to share information. But it is also becoming clear that when local news contracts it creates a lower quality information environment. Effectively, an information vacuum is formed that is often filled by national news (which tends to be more polarizing) and social media (which includes more rumor and misinformation).

The Ouray County Plaindealer is an illustrative case. The only news outlet serving the about 5,000 residents of Ouray County in southwest Colorado, the paper closely followed the DUI arrest of a local sheriff. The paper followed up on that reporting to expose earlier arrests while the sheriff was working for another police department, prior to him coming to Ouray County. The community organized its first-ever recall election in 2020, even amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Erin McIntyre, one of the paper’s publishers, said she doubts if the community would have mustered the energy to pursue the recall without the paper’s sustained reporting. The sheriff was ousted with more than 90% of the vote. This is precisely the civic contribution local news outlets can offer communities — spurring community action to right local wrongs. Yet, the Plaindealer also illustrates the pitfalls of addressing broadband deserts without building or strengthening access to local news. McIntyre wrote in a survey deployed by Rebuild Local News, “We have seen increased competition from websites like Nextdoor and Facebook, where people think they’re getting their news but are just spreading rumors. These online cesspools have created a nightmare for us, trying to hold on to our niche as the vetted, reliable source of local news.”

Broadband can provide access to information to communities, but without strong local news in those communities, the information is not likely to fulfill the objectives of digital equity: That citizens have the ability to be full digital participants in their cultural and civic institutions.

Digital equity requires support services that local news organizations can help provide

Some local news organizations are already pursuing the goals of digital equity in their community, not only in the journalism they provide, but by teaching residents digital skills and sharing information about broadband access and affordability.

Six of the 27 outlets said they already participate in digital and media literacy training within their communities. Another two said they help community members troubleshoot digital technology and help community members bring broadband to their community. Twenty five of the 27 local news outlets we reached out to said they would be open to implementing digital literacy, access or adoption programs if funds were made available.

El Tímpano, a news outlet that serves the Latino and Mayan communities in the Bay Area of California, has partnered with local organizations to help spread awareness about how residents can access affordable broadband and computers as well as how to register in computer classes. It has worked with The Town Link Digital Inclusion Program to build digital skills, address barriers to internet access — including affordability — and decrease the digital divide in Oakland, California. It also educates local Latino immigrants on mis/disinformation, why Latino and Spanish-speaking communities are often targeted and what they can do to defend their communities from the spread of misinformation.

In Dallas, the Dallas Free Press shares information about broadband providers and access with historically redlined communities. The paper has also dedicated significant resources to reporting on the efficacy of broadband investments in Dallas, providing critical information to both local officials and local residents about whether programs are being effective in addressing digital equity. A radio station told Rebuild Local News that after providing dial up internet to their audience, they now have a partnership to offer email addresses to community members who need them.

While providing reporting on civic affairs tends to increase engagement, some news outlets have gone to extra lengths to encourage civic activity among local residents. Black by God, a newspaper that serves the Black community in West Virginia launched a pilot to deploy local community members as “folk reporters.” Modeled after the Documenters Network, which was launched by Chicago-based nonprofit newsroom City Bureau, these folk reporters attend state legislature meetings that often go un- or under-covered by other news outlets. Kate Mulligan, a public health professor at the University of Toronto, argues that projects like this are “a way to bridge digital divides that goes beyond digital access and digital literacy to support and sustain online participation as a key facet of digital inclusion.” Founder of Black by God, Crystal Good is also a fellow with Black Churches 4 Digital Equity, a civil rights organization pursuing digital equity in Black communities across the United States.

Given local news outlets’ role as drivers of civic information combined with evidence that shows the willingness of news outlets to advance their community’s digital needs, local news providers are ideal partners in the effort to connect residents.

Recommendations

State Digital Equity Plans

“What criteria/factors/outcomes should communities focus on in their review”

- Access to professional local news and information. Key questions: How many local reporters per population are there? Are the important critical information needs being met? How many residents are being trained to participate in local news gathering?

- Civic engagement. Key questions: What are the participation levels in civic institutions? What is the knowledge of local affairs by residents? How likely is a resident to contact a local elected official? How likely are residents to contact or engage with local elected officials?

Capacity Grant Program

“How should NTIA define success for the Capacity Grant Program? What outcomes are most important to measure? How should NTIA measure the success of the Capacity Grant Program, including measures and methods?”

- Access to local news and information. Metrics: Number of local reporters. Coverage of important civic issues. In cases where there is no news organization already, it could be measured by the creation of at least one new local news organization.

- Civic engagement. Growth in participation in civic activities. Growth in voter turnout. Increase in knowledge about public officials and issues. Increased likelihood to contact a local elected official. Number of residents who participated in programs to cover local government meetings or other civic events.

Competitive Grant Program

“What kind of activities or projects should the Assistant Secretary consider for inclusion in eligible projects and activities for the Competitive Grant Program”

- Local news initiatives. Initiatives that strengthen basic local reporting in that area, including by allowing the hiring of local reporters and/or training local residents to report on local civic affairs. In cases where there is no news organization already, it could be measured by the creation of at least one new local news organization.

- Civic engagement programs. Programs that bring together members of the community to discuss local issues and developments. This may include developing community-wide digital equity goals.

- Use of local news organizations to promote digital literacy or adoption. Digital literacy or digital navigator trainings. Special coverage of digital equity efforts. Partnerships with internet service providers to drive adoption efforts.

“ What group or groups that are not already listed should the Assistant Secretary consider to be eligible to apply for the Competitive Grant Program?”

- Local news organizations (for profit, nonprofit, community, digital, public). As argued above, we strongly recommend that local news organizations, regardless of business model or medium, be included in the list of groups eligible to apply for the Competitive Grant Program.

“What are examples of past or current evidence-based or evidenced-informed digital equity and /or inclusion projects or other relevant or similar projects that NTIA can showcase as a part of its technical assistance efforts to support applications in identifying promising or evidence-based project models, partnerships, activities, and strategies to consider, replicate, and leverage lessons learned as applicable?”

Conclusion

Years of scholarship since the expansion of the internet has shown the limits of affecting democratic participation via internet access alone. Although access to high-speed broadband services and the skills to use those services is crucial to full civic participation, the internet alone has failed to deliver on its democratic promises. Professors Danny Hayes and Jennifer Lawless wrote in their book News Hole: The Demise of Local Journalism and Political Engagement

“The obvious difficulty for the internet-as-savior account is that Americans’ knowledge of local government and participation in local elections have been declining as the internet has become a ubiquitous feature of modern life.”

One reason for this asymmetry, the pair wrote, is “the nature of the internet — and the dominance of web traffic by Google, Facebook, and Amazon — has served to reduce Americans’ exposure to local information, not increase it.” Local information is a key component of civic participation and the ability to be a civic participant is a key component of digital equity.

The communities that are least likely to have local news are those that are rural, poor or speak a language other than English. Professor Abernathy’s research shows that news deserts also tend to underperform when it comes to educational attainment. These indicators overlap with the communities least likely to have adequate or affordable broadband. Indeed, our comparison with news desert and broadband desert data show these double deserts in more than two dozen states.

Yet, addressing the challenges to broadband access while failing to build and fortify local news will not fulfill the promises of digital equity. We must not only provide high-speed access to the internet but also connect them to local, vetted and trustworthy information that can strengthen communities.